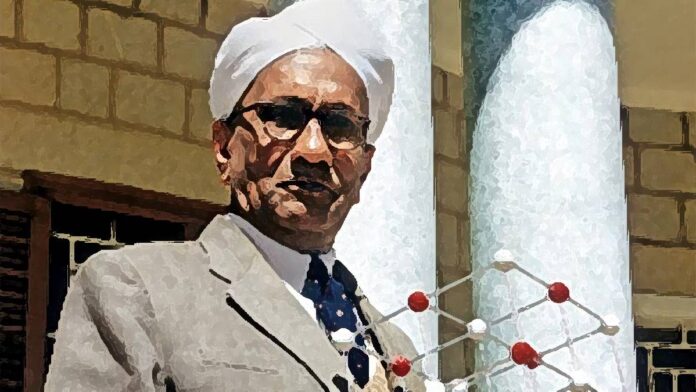

CV Raman’s full name is Sir Chandrashekhar Venkata Raman. CV Raman was a great physicist in India. He is known for the intensity of his work in light scattering. When he and his student KS Krishnan passed sunlight through a transparent collector using a spectrograph, they observed that the light that passed through that fine collector changed the wavelength and frequency of the diffracted light. Light passing through a transparent material is called modified light scattering. The physics test on this was called the Raman effect or Raman scattering. CV Raman was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1930 for this discovery. CV Raman was the first person from Asia to be awarded the Nobel Prize. Know more about his life in this article.

Contents

C.V. Raman’s Birth

C.V. Raman was born in the Tamil Brahmin family of Tamil Nadu. Raman was a premature child. He received his primary, secondary and higher secondary education from St. Aloysius Anglo Indian High School at 11 to 12 years old. Raman did his post-graduation in physics by securing a top position at Presidency College.

Early life and education

CV Raman was born in Tiruchirappalli Madras (Tamil Nadu). He was born in a Hindu Tamil Brahmin family. His mother’s name was Parvati Ammal, and his father was Chandrashekhar Ramnath Iyer. His father was a teacher at the local high school. His parents had eight children. He was among the elder siblings in second place. He said that he was born with a copper spoon in his mouth because his father was doing an excellent job of Rs 10,000 at the time of his birth and was appointed as a Faculty in Physics at Narasimha Rao College in Andhra Pradesh. CV Raman passed the matriculation examination at the age of 11 at the Anglo-Indian High School. At the age of 13 passed the Intermediate from the medium of arts with the first position in the Board of Secondary Education of Andhra Pradesh.

In 1902 Raman Rahman joined the Madras Presidential University (Chennai), where his father was appointed to teach mathematics and physics. He completed his B.A degree from Madras University in 1904. He obtained his first degree from Madras University and won gold medals in Physics and English. When he was 18 years old, he published his first scientific paper on the fine particles of rectangular holes and their size, why they are so, and their tectonic edges.

Seeing Raman’s qualifications and his physics teacher’s riches, skill, and ability, he was encouraged by Llewellyn Jones to continue research in England. Jones arranged Raman’s physical inspection with Colonel (Sir Gerald) Gifford. Unfortunately, Raman often had poor health and was considered “physically weak.” When it came to going to England for research, he said, “I am going to die of tuberculosis.”

Career

Raman joined the Indian Financial Services Center in 1902 and made his organization one of the best service organizations in India. Raman followed suit to study abroad and, in early February 1907, received orders from the Indian Financial Service to change exams. After this, he was sent to Kolkata in June 1907 as Chief Assistant Accountant.

He was greatly influenced by the Indian Association for the Advancement of Science, the first research institute established in India, which was founded for the first time in India in 1876. Raman’s article “Newton’s Rings in Polarized Light,” published in Nature in 1907, became the first article of the Institute. The work prompted the IACS to issue a journal, Bulletin of the Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science, in 1909, with Raman making significant contributions.

In 1909, Raman Rangoon went to British Burma to become a finance officer. A few months later, his father died of a severe illness, so he had to return to Chennai. He lived there for one year after his father’s death. Shortly after joining Rangoon, he moved to Nagorno, Maharashtra, India, in 1910. In 1911 he was promoted to General Accountant and went to Calcutta after serving one year.

In 1915, the University of Calcutta started recruiting scholars under the leadership of Raman Ji under IACS. Late Shri Sudhangsu Kumar Banerjee became the Director-General of the India Meteorological Department and became a Ph.D. scholar under Ganesh Prasad, the first student of C.V.Raman. He guided many students till 1919. In 1919, he got the higher rank of IACS. After coming to this institution, Raman said that this was the best period of his life.

Raman Palit was elected Professor of Physics at the University of Calcutta. This proposal was founded by the donor Sir Tarakuna Palit in 1913. The Senate was appointed to address the meeting checklist on January 30, 1914. Before 1914, Raman became the first Palit Professor of Physics as a second option, but the post was postponed due to the expansionist World War I. He became Professor Forever in 1917. When he reluctantly resigned as a civil servant in 1914 after serving ten years at the Raja Bazar Science College built by the University of Calcutta. His salary as a professor was about half that of that time. However, to his advantage, his terms as a professor were clearly shown in the report that he had entered the college.

In 1943, Raman and his alumnus Panchapaksha Krishnamurthy founded the Travancore Chemical and Manufacturing Company Limited. The company’s name was changed to TCM Limited in 1996, and it is one of India’s earliest manufacturers of organic and inorganic chemicals. In 1947, Raman was appointed the first National Professor by the newly independent Government of India. In 1948, Raman established the Raman Research Institute in Bangalore. Here he also became a director and worked till 1970.

CV Raman’s research

His first research on the description of light was published in 1906. He got acquainted with the Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science as an Assistant Accountant General in the Indian Financial Service, Calcutta. With the help of this, he obtained permission to do independent research. With his help, he made a unique contribution to understanding light and sound—Ashutosh Mukherjee at Calcutta University in 1917 at Rajabazar Science College, CV. Raman was appointed as Professor of Physics for the first time.

Once when he was going on his first trip to Europe, he saw the sea was blue in his mind, he was curious to know, as well as he saw that when the airplane was flying in the sky, he saw a thing like smoke. I noticed that when the aircraft was moving in front of it, it was getting pinched. He researched the above events and, in 1926, laid the foundation of the Indian General of Physics. He moved to Bangalore in 1933 to become the first director of the Indian Institute of Science. In 1993, he established his Indian Academy of Sciences, followed by the Raman Research Institute in 1948, and continued to do the same work throughout his lifetime. He discovered the Raman effect on February 28, 1928, which is celebrated as National Science Day in the history of India. In 1954, he was awarded the Bharat Ratna, the highest civilian award, by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. He later disbanded the medal in protest against Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s policies on scientific research.

Scientific Contribution

On a voyage to Europe in 1921, Raman keenly noticed the blue color of the glaciers and the Mediterranean Sea. He was curious to know the reason for the blue color. Once Raman returned to India, he did many experiments regarding the scattering of light by water and transparent blocks of ice. According to the results, he established a scientific explanation of the blue color of seawater and the sky.

There is a fascinating incident that served as the inspiration for the discovery of the Raman Effect. Raman was busy working on a December evening of 1927 when his student K.S. Krishnan (who later became director of the National Physical Laboratory, New Delhi) informed him that Professor Compton had won the Nobel Prize for X-ray scattering. This brought some thoughts to Raman’s mind. He remarked that if the Compton effect applies to X-rays, the same should be valid for light. So he did some experiments to establish his opinion.

Raman used monochromatic light from mercury that entered a transparent material and was allowed to fall on a spectrograph to record its spectrum. Raman detected new lines in the range called ‘Raman Lines.’ A few months later, Raman presented his discovery of the ‘Raman Effect’ at a meeting of scientists in Bangalore on March 16, 1928, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1930.

The ‘Raman Effect’ is essential in analyzing chemical compounds’ molecular structure. A decade after its discovery, the design of about 2000 compounds was studied. Thanks to the invention of the laser, the ‘Raman Effect’ has proved to be a handy tool for scientists. Some of Raman’s other interests were the physiology of human vision, the optics of colloids, and electric and magnetic anisotropy.

CV Raman became a Fellow of the Royal Society of London in 1924. A year later, he founded the Raman Research Institute near Bangalore, where he continued scientific research until his death; his honest advice to aspiring scientists was that “scientific research requires independent thinking and hard work, equipment or not.”

Death

In late October 1970, Raman suffered a heart attack and collapsed in his laboratory. He was taken to the hospital, where doctors treated him and told him he would not survive more than 4 hours. The doctors said that he lived among his followers for the rest of the time to live more. Two days before Raman’s death, one of his former students pointed out that the Academy’s critical journal reflects the quality of the ongoing science in this field and what science is contained in it. That night Raman met the management team in his bedroom lab and told them about the lab’s success. His wife wanted a brief cremation without procession until his death. He died of natural causes on November 8, 1970, at 82.

Sources

- “Raman effect” was Archived on October 24, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. Collins English Dictionary.

- Bhagavatam, Suri (1971). “Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman, 1888-1970”. Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 17: 564–592. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1971.0022.

- Singh, Rajinder; Riess, Falk (1998). “Sir C. V. Raman and the story of the Nobel prize.” Current Science. 75 (9): 965–971. JSTOR 24101681.

- “CV Raman Birth Anniversary 2020: Interesting Facts About The Nobel Laureate”. NDTV.com.

- Prasar, Vigyan. “Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman A Legend of Modern Indian Science.” Government of India.

- “CV RAMAN: A Creative Mind Par Excellence.” Hindustan Times. July 8, 2019.

- Jayaraman, Aiyasami (1989). Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman: A Memoir. Bengaluru: Indian Academy of Sciences. p. 4. ISBN 978-81-85336-24-4. OCLC 21675106.

- Clark, Robin J. H. (2013). “Rayleigh, Ramsay, Rutherford and Raman – their connections with, and contributions to, the discovery of the Raman effect.” The Analyst. 138 (3): 729–734. Bibcode:2013Ana…138..729C. doi:10.1039/C2AN90124B. PMID 23236600.

- Mukherji, Purabi; Mukhopadhyay, Atri (2018), “Sir Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman (1888–1970)”, History of the Calcutta School of Physical Sciences, Singapore: Springer Singapore, pp. 21–76, doi:10.1007/978-981-13-0295-4_2, ISBN 978-981-13-0294-7

- Raman, C.V. (1906). “LV. Unsymmetrical diffraction-bands due to a rectangular aperture.” The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 12 (71): 494–498. doi:10.1080/14786440609463564.

- “About C V Raman Life, Achievements and Paper Publications.” Indore [M.P.] India. February 13, 2020.

- Raman, C.V. (1907). “LVIII. The curvature method of determining the surface-tension of liquids.” The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 14 (83): 591–596. doi:10.1080/14786440709463720.

- Rayleigh, Lord (1907). “X. On the relation of the sensitiveness of the ear to pitch, investigated by a new method.” The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 14 (83): 596–604. doi:10.1080/14786440709463721.

- Singh, Rajinder; Riess, Falk (2004). “The Nobel Laureate Sir Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman FRS and His Contacts with the British Scientific Community in a Social and Political Context.” Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 58 (1): 47–64. doi:10.1098/rsnr.2003.0224. JSTOR 4142032. S2CID 144713213.

- Jayaraman, Aiyasami (1989). Op cit. p. 5. OCLC 21675106.

- Singh Rajinder (2002). “C.V. Raman and the Discovery of the Raman Effect.” Physics in Perspective. 4 (4): 399–420. Bibcode:2002PhP…..4..399S. doi:10.1007/s000160200002. S2CID 121785335.

- Banerjee, Somaditya (2014). “C. V. Raman and Colonial Physics: Acoustics and the Quantum.” Physics in Perspective. 16 (2): 146–178. Bibcode:2014PhP….16..146B. doi:10.1007/s00016-014-0134-8. S2CID 121952683.

- Biwas, Arun Kumar (2010). “Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science: A Nation’s Dream, 1969-1947”. In Dasgupta, Uma (ed.). Science and Modern India: An Institutional History, c. 1784-1947. Delhi: Pearson. pp. 69–116. ISBN 978-93-325-0294-9. OCLC 895913622.

- Raman, C. V. (1907). “Newton’s rings in polarised light.” Nature. 76 (1982): 637. Bibcode:1907Natur..76..637R. doi:10.1038/076637b0. S2CID 4035854.

- Basu, Tejan Kumar (2016). The Life and Times of C.V. Raman. Prabhat Prakashan. pp. 22–23. ISBN 978-81-8430-362-9.

- C.V. Raman: A Pictorial Biography. Indian Academy of Sciences India. 1988. p. 3. ISBN 978-81-85324-07-4.

- Mukherji, Purabi; Mukhopadhyay, Atri (2018). History of the Calcutta School of Physical Sciences. Singapore: Springer. p. 30. ISBN 978-981-13-0295-4. OCLC 1042158966.

- “C.V. Raman.” OSA. The Optical Society, Washington, DC, USA. June 12, 2013.

- Blanpied, William A. (1986). “Pioneer Scientists in Pre‐Independence India.” Physics Today. 39 (5): 36–44. Bibcode:1986PhT….39e..36B. doi:10.1063/1.881025.

- Blanpied, William A. (1986). “Pioneer Scientists in Pre‐Independence India.” Physics Today. 39 (5): 36–44. Bibcode:1986PhT….39e..36B. doi:10.1063/1.881025.

- Jayaraman, Aiyasami; Ramdas, Anant Krishna (1988). “Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman”. Physics Today. 41 (8): 56–64. Bibcode:1988PhT….41h..56J. doi:10.1063/1.881128.

- “C.V. Raman The Raman Effect – Landmark.” American Chemical Society.

- “Indian Journal of Physics.” 1926.

- Raman, C. V. (1928). “A new radiation.” Indian Journal of Physics. 2: 387–398.

- “Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science (1876–)”. Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science.

- Reddy, Venkatarama; Guttal, Vishwesha. “Indian Institute of Science.” The Conversation.

- Uma, Parameswaran (2011). C.V. Raman: A Biography. New Delhi: Penguin Books India. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-14-306689-7. OCLC 772714846.

- “About us.” TCM Limited – Official website.

- Mascarenhas, K. Smiles (2013). “Sir C.V. Raman – Icon of Indian Science.” Science Reporter. 50 (11): 21–25.

- Raman, C.V. (1916). “XLIII. On the “wolf-note” in bowed stringed instruments.” The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 32 (190): 391–395. doi:10.1080/14786441608635584.

- Raman, C.V. (1921). “On some Indian stringed instruments” (PDF). Proceedings of the Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science. 7: 29–33.

- Raman, C.V.; Dey, Ashutosh (1920). “X. On the sounds of splashes.” The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 39 (229): 145–147. doi:10.1080/14786440108636021.

- Raman, C.V. (1920). “Experiments with mechanically-played violins” (PDF). Proceedings of the Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science. 6: 19–36.

- Raman, C. V.; Kumar, Sivakali (1920). “Musical Drums with Harmonic Overtones.” Nature. 104 (2620): 500. Bibcode:1920Natur.104..500R. doi:10.1038/104500a0. S2CID 4159476.

- Raman, C.V.; Banerji, B. (1920). “On Kaufmann’s theory of the impact of the pianoforte hammer.” Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Containing Papers of a Mathematical and Physical Character. 97 (682): 99–110. Bibcode:1920RSPSA..97…99R. doi:10.1098/rspa.1920.0016.

- Raman, C.V. (1922). “On whispering galleries” (PDF). Bulletin of the Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science. 7: 159–172.

- Banerjee, Somaditya (2014). “C. V. Raman and Colonial Physics: Acoustics and the Quantum.” Physics in Perspective. 16 (2): 146–178. Bibcode:2014PhP….16..146B. doi:10.1007/s00016-014-0134-8. S2CID 121952683.

- Raman, C.V. (1919). “LVI. The scattering of light in the refractive media of the eye.” The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 38 (227): 568–572. doi:10.1080/14786441108635985.

- Anon. (2009). “This Month in Physics History: February 1928: Raman scattering discovered”. APS News. 12 (2): online.

- Buchanan, J. Y. (1910). “Colour of the Sea.” Nature. 84 (2125): 87–89. Bibcode:1910Natur..84…87B. doi:10.1038/084087a0.

- Rayleigh, J.W.S. (1910). “Colours of Sea and Sky.” Nature. 83 (2106): 48–50. Bibcode:1910Natur..83…48.. doi:10.1038/083048a0.

- Rayleigh, Lord (1899). “XXXIV. On the transmission of light through an atmosphere containing small particles in suspension, and on the origin of the blue of the sky.” The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 47 (287): 375–384. doi:10.1080/14786449908621276.

- Stetefeld, Jörg; McKenna, Sean A.; Patel, Trushar R. (2016). “Dynamic light scattering: a practical guide and applications in biomedical sciences.” Biophysical Reviews. 8 (4): 409–427. doi:10.1007/s12551-016-0218-6. PMC 5425802. PMID 28510011.

- Raman, C. V. (1921). “The Colour of the Sea.” Nature. 108 (2716): 367. Bibcode:1921Natur.108..367R. doi:10.1038/108367a0. S2CID 4064467.

- Mallik, D. C. V. (2000). “The Raman Effect and Krishnan’s Diary.” Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 54 (1): 67–83. doi:10.1098/rsnr.2000.0097. JSTOR 532059. S2CID 143485844.

- Raman, C.V. (1922). “On the molecular scattering of light in water and the color of the sea.” Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Containing Papers of a Mathematical and Physical Character. 101 (708): 64–80. Bibcode:1922RSPSA.101…64R. doi:10.1098/rspa.1922.0025.

- Ramanathan, K.R. (1923). “LVIII. On the color of the sea.” The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 46 (273): 543–553. doi:10.1080/14786442308634277.

- Ramanathan, K. R. (March 1, 1925). “The Transparency and Color of the Sea.” Physical Review. 25 (3): 386–390. Bibcode:1925PhRv…25..386R. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.25.386.

- Braun, Charles L.; Smirnov, Sergei N. (1993), “Why is water blue?” (PDF), Journal of Chemical Education, 70 (8): 612–614, Bibcode:1993JChEd..70..612B, doi:10.1021/ed070p612.

- Singh, Rajinder (1 March 2018). “The 90th Anniversary of the Raman Effect” (PDF). Indian Journal of History of Science. 53 (1): 50–58. doi:10.16943/ijhs/2018/v53i1/49363.

- Krishnan, K.S. (1925). “LXXV. On the molecular scattering of light in liquids.” The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 50 (298): 697–715. doi:10.1080/14786442508634789.

- Compton, Arthur H. (May 1923). “A Quantum Theory of the Scattering of X-Rays by Light Elements.” Physical Review. 21 (5): 483–502. Bibcode:1923PhRv…21..483C. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.21.483.

- Raman, C. V. (1927). “Thermodynamics, Wave-theory, and the Compton Effect.” Nature. 120 (3035): 950–951. Bibcode:1927Natur.120..950R. doi:10.1038/120950a0. S2CID 29489622.

- Ramdas, L. A. (1973). “Dr. C. V. Raman (1888-1970) , Part II”. Journal of Physics Education. 1 (2): 2–18.

- Singh, Rajinder (2002). “C. V. Raman and the Discovery of the Raman Effect.” Physics in Perspective. 4 (4): 399–420. Bibcode:2002PhP…..4..399S. doi:10.1007/s000160200002. S2CID 121785335.

- Raman, C. V.; Krishnan, K. S. (1928). “A new type of secondary radiation.” Nature. 121 (3048): 501–502. Bibcode:1928Natur.121..501R. doi:10.1038/121501c0. S2CID 4128161.

- “How is C.V Raman connected with National Science Day.” Business Insider. February 28, 2020.

- Long, D. A. (1988). “Early history of the Raman effect.” International Reviews in Physical Chemistry. 7 (4): 317–349. Bibcode:1988IRPC….7..317L. doi:10.1080/01442358809353216.

- Singh, Rajinder (2018). “How costly was Raman’s equipment for discovering the Raman effect?” (PDF). Indian Journal of History of Science. 53 (4): 68–73. doi:10.16943/ijhs/2018/v53i4/49527.

- “Raman Effect Visualised.” Archived from the original.

- Jagdish, Mehra; Rechenberg, Helmut (2001). The Historical Development of Quantum Volume 6 Part 1. New York: Springer. p. 360. ISBN 978-0-387-95262-8. OCLC 76255200.

- Pringsheim, Peter (1928). “Der Ramaneffekt, ein neuer von C. V. Raman entdeckter Strahlungseffekt”. Die Naturwissenschaften (in German). 16 (31): 597–606. Bibcode:1928NW…..16..597P. doi:10.1007/BF01494083. S2CID 30433182.

- Wood, R. W. (1929). “The Raman Effect with Hydrochloric Acid Gas: the ‘Missing Line.'”. Nature. 123 (3095): 279. Bibcode:1929Natur.123Q.279W. doi:10.1038/123279a0. S2CID 4121854.

- “C.V. Raman The Raman Effect – Landmark.” American Chemical Society.

- Venkataraman, G. (1995), Raman and His Effect, Orient Blackswan, p. 50, ISBN 978-81-7371-008-7.

- Singh, Binay (8 November 2013). “BHU preserves CV Raman’s association with the university.” The Times of India.

- Prakash, Satya (20 May 2014). Vision for Science Education. Allied Publishers. p. 45. ISBN 978-81-8424-908-8.

- Raman, C. V.; Bhagavantam, S. (1932). “Experimental Proof of the Spin of the Photon.” Nature. 129 (3244): 22–23. Bibcode:1932Natur.129…22R. doi:10.1038/129022a0. hdl:10821/664. S2CID 4064852.

- C. V. Raman, N. S. Nagendra Nath, “The diffraction of light by high-frequency sound waves. Part I”.

- Cheng, Qixiang; Bahadori, Meisam; Glick, Madeleine; Rumley, Sébastien; Bergman, Keren (2018). “Recent advances in optical technologies for data centers: a review.” Optica. 5 (11): 1354–1370. Bibcode:2018Optic…5.1354C. doi:10.1364/OPTICA.5.001354.

- Raman, C. V. (1942). “The nature of the liquid state.” Current Science. 11 (8): 303–310. JSTOR 24213500.

- Raman, C. V. (1942). “Reflexion of X-Rays with Change of Frequency.” Nature. 150 (3804): 366–369. Bibcode:1942Natur.150..366R. doi:10.1038/150366a0. S2CID 222373.

- Raman, C. V. (1948). “Dynamic X-ray reflections in crystals” (PDF). Current Science. 17: 65–75.

- Raman, C. V. (1943). “The structure and properties of diamond” (PDF). Current Science. 12 (1): 33–42. JSTOR 24208172.

- Raman, C. V.; Jayaraman, A. (1950). “The structure of labradorite and the origin of its iridescence.” Proceedings of the Indian Academy of Sciences, Section A. 32 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1007/BF03172469. S2CID 128235557.

- Raman, C. V.; Jayaraman, A. (1953). “The structure and optical behavior of iridescent agate.” Proceedings of the Indian Academy of Sciences, Section A. 38 (3): 199–206. doi:10.1007/BF03045221. S2CID 198139210.

- Raman, C. V.; Krishnamurti, D. (1954). “The structure and optical behavior of pearls.” Proceedings of the Indian Academy of Sciences, Section A. 39 (5): 215–222. doi:10.1007/BF03047140. S2CID 91310831.

- Landsberg, G.; Mandelstam, L. (1928). “Eine neue Erscheinung bei der Lichtzerstreuung in Krystallen”. Die Naturwissenschaften (in German). 16 (28): 557–558. Bibcode:1928NW…..16..557.. doi:10.1007/BF01506807. S2CID 22492141.

- Usanov, D. A.; Anikin, V. M. (2019). “The Sixth Congress of Russian Physicists in Saratov (August 15, 1928)”. Izvestiya of Saratov University. New Series. Series: Physics. 19 (2): 153–161. doi:10.18500/1817-3020-2019-19-2-153-161.

- Singh, Rajinder; Riess, Falk (2001). “The Nobel Prize for Physics in 1930 – A close decision?”. Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 55 (2): 267–283. doi:10.1098/rsnr.2001.0143. S2CID 121955580.

- Fabelinskiĭ, Immanuil L (October 31, 2003). “The discovery of combination scattering of light in Russia and India.” Physics-Uspekhi. 46 (10): 1105–1112. doi:10.1070/PU2003v046n10ABEH001624.

- Fabelinskii, I. L. (1990). “Priority and the Raman effect.” Nature. 343 (6260): 686. Bibcode:1990Natur.343..686F. doi:10.1038/343686a0. S2CID 4340367.

FACT CHECK: We strive for accuracy and fairness. But if you see something that doesn’t look right, please Contact us.

DISCLOSURE: This Article may contain affiliate links and Sponsored ads, to know more please read our Privacy Policy.

Stay Updated: Follow our WhatsApp Channel and Telegram Channel.